African music is a bottomless well; you could spend a lifetime barely skimming its surface. But for a crash course, meet

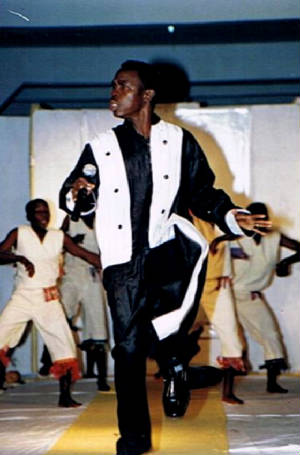

George Okudi.

A pastor with the Holy Ghost Revival Centre in Kasubi, Kampala, in Uganda, Okudi is also a musician of staggering pedigree.

In 2003, the KORA Awards (think African Grammy) named him Best Male Artiste in Africa — as in the whole continent. Last

year, he was nominated for a KORA lifetime achievement award. He's only 38.

The shorthand: A musician to be reckoned with, even if you can't find his music on Amazon.

And he will be in Greenville on Saturday, performing at 7 p.m. at Faith & Victory Church, as a fund-raiser organized

by Ugandan physician Dr. Sylvester Odeke of East Carolina University's Brody School of Medicine (see today's Daily Reflector

story on page A1). The concert is to raise money to build a 65-bed hospital in rural Uganda.

Okudi is doing a short U.S. tour in the absence of his sprawling band, which once topped out at 90 members, but which normally

numbers about 30. He will appear solo at Faith & Victory, against an aural backdrop of prerecorded tracks.

"It's gonna be like a one-man show," Okudi said in a recent phone interview from Washington, D.C. "But trust me, it's going

to be interesting."

To be sure. No less than the Ugandan ambassador to the United States, Perezi Kamunanwire, was slated to drop in, his visit

canceled due to a death in the family. Uganda's Deputy Chief of Mission Charles Ssentongo will be here in the ambassador's

stead.

In conversation, Okudi is unfailingly polite in that distinctly African manner. He's also lived the public life long enough

that he has a tendency to talk at first in sound bites that, while factual, are often spun in a layer of gloss:

"I am the product of African art," he said at the outset of our interview. "I had the opportunity to grow up in a very

simple African home. A rural, authentic African setting, whereby people lived by looking after cows and drinking milk, (as)

pastoral agriculturalists."

He likes to say that he was inspired to become a musician by hearing the birds in the field.

A simple, happy picture. It's also a vastly incomplete one.

George Okudi literally would not exist without music.

"My mother was in a school choir, and my father, who was actually a civil engineer, was visiting the school, and that's

how he saw my mother," Okudi explained. "She just blew him off his feet. And that's how they got married."

Yet another idyllic picture. The rest of it isn't so sweet.

A poor phone connection during our interview led Okudi to mishear a question about his father's having "passed away" early,

and the singer opened up a side of himself he had surely not meant to discuss.

"Yes," he responded. "My father cast me out at a young age because of his social life. He was kind of like a drunkard.

My father was the kind of man who did not take care of his family."

By then, Okudi's parents had divorced, his mother having moved to the eastern city of Pallisa from their village in north

Uganda. Okudi found himself living on his own long before the death of his father, in 1984.

"I grew up kind of like an orphan most of my life," he said. "I was living in a very, very terrible state."

Not everything was bad, however. In fact, some of Okudi's early experiences were among the best of his life. It was in

that time he developed "a very strong musical affection," he said.

Being enthralled by the chirping of birds was only part of it.

"I used to take out people's cows to graze in this huge savannah land, where you just literally disappear in the middle

of nowhere," Okudi recalled. "All you have for entertainment is to hear different birds bringing up sounds. It really brings

out a deep meditation for you."

But the end of the workday, when all the tools were stored and the cows and oxen penned, offered music of a very different

form.

North Uganda is "like the southern Sudan," Okudi explained. "Those people have got a very deep culture of music. They are

very social people who like to gather together and produce music as a form of entertainment.

"When the sun goes down and that gentle breeze in the evening begins to blow, people bring out their musical instruments."

The whole village would join in on such traditional instruments as the malimba (similar to a xylophone) and kalimba (commonly

called a thumb piano).

"It's such a very beautiful thing," Okudi said. "In the night, they use the moonlight to bring out the light."

Those youthful musical experiences became what Okudi calls "a permanent scar in my music life," offsetting some of the

psychic scars of poverty and lack of family.

When Okudi's mother learned of her son's struggles in the absence of his father, she arranged for him to come live with

her in Pallisa.

Upon his arrival, Okudi was overwhelmed by the music he encountered there: distinctly African genres with distinctly African

names like soukous, zouk, lingala.

"That music just sent me mad," he said. "I was almost crazy! It was just way beyond my imagination. I kind of became like

a music fanatic then."

He had already begun performing by that point, but considered it a lark, nothing serious, and not on account of his having

any unique talent.

That all changed at about the age of 16, when Okudi answered the call to become a Christian.

"By 16, I had gone through it all. I knew what it meant to go without food and family, and how to sleep without a blanket

on your body," he said. "I knew how to survive. I knew how to make my own money, to go work for people. I had already experienced

a lot in life.

"I was seeking somewhere for solace, and to get some kind of rest, you know? Things were not working out very well."

His embrace of the church was immediate.

"I'm the kind of person who, when I give myself (to) something, I give it my all," he said. "I really decided I wanted

to find God."

That searching also led him to find himself as a musician.

At the time of his conversion, Okudi stopped singing for about three years, "just trying to grasp a new life," he explained.

Then, at a Christian event he was attending in 1986, organizers asked if anyone wanted to sing during a program break.

Okudi stood up, and sang.

"And the crowd goes wild," he recalled with a chuckle.

Soon after, he was being asked to sing at churches every Sunday. Okudi realized he had a decision to make. It was time

to devote himself not only to God, but also to music.

Okudi's music is exalting as only the best African pop can be. Choir-like vocals rise up in affirmation. Guitars seem to

dance. Even the slowest songs have a kind of bounce to them.

His songs take all of Africa as their palette: fluid West African guitar, sinewy Arabic rhythms, South African township

singing a la Ladysmith Black Mambazo (the Life Savers guys), the giddy call and response of Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens,

the sprawling instrumentation of Juluka.

But Okudi is more democratic still, spicing up his African art with hints of Latin styles, and nods to reggae, ska, calypso

and even American hip-hop.

With him, that's a good thing. With other, less-sensitive artists, such inclusiveness can be ruinous.

American music forms — in particular, contemporary urban styles — have infiltrated traditional music the world

over. Even the third generation of singers in Black Mambazo attempted a rap cut a few years ago. That was a bad thing.

Because mostly, this cultural colonialism asserts itself at the expense of what's best in native art (particularly ironic

in African music, since most American music forms have very obvious roots in Mother Africa).

Okudi has seen that up close. Many musicians in east Africa, particularly in the cities, suffer from identity problems,

he said.

"So what most of the young people do, because of the craving for being cool — they love the word 'cool' — (is)

completely borrow everything from the Western styles," he explained. "However, they cannot do it as good as the guys who do

it here (in the United States, where) they've grown up with it."

Okudi's own first songs were very Western, he said. "They were not authentic African songs."

It was during a tour of England in 1995 that a fan encouraged him to devote himself to making his music less Western, and

more African.

Okudi heeded the advice, undertaking a serious study of African music, spanning the continent.

"I asked myself, 'Is there a way to make the world feel what we used to feel in those villages?'"

His soul searching led to the 2003 album "Wipolo." The one that made him an international star, the male musician to beat

in Africa.

"The idea behind that album," Okudi said, "is trying to make you feel what we used to feel in those evenings when all the

people finished working, and there's no more commitment, and there's only the moonlight left for you to enjoy."

Contact Frank W. Rabey, features editor for The Daily Reflector, at 329-9575 or frabey@coxnc.com.

Pastor George Okudi is one of the many artists on our site who refuses to fit neatly into one single category. As a pastor of an evangelical

church in Kampala, Uganda, Pastor Okudi regularly ministers to the spiritual needs of his thousands of congregants. As a pop

icon and winner of multiple KORA awards (including Best Male Artist for 2003 for the whole African continent), George Okudi

regularly packs the halls and sings to crowds of tens of thousands of people. His song 'Wipolo' is a clever blend of both

of these sides of his life. A straight up modern african pop piece, this song is guaranteed to get anyone moving. This song

is also the song that won Okudi the PAM (Pearl of Africa) Award for best song, won the FM Best Single Award, and launched

Okudi to the KORA awards in 2003. So for those of you who know the song, but have not been able to find a copy, get it now!

For those of you who have never heard it, join the 800 million Africans who have by getting your own copy now!

Pastor George Okudi is one of the many artists on our site who refuses to fit neatly into one single category. As a pastor of an evangelical

church in Kampala, Uganda, Pastor Okudi regularly ministers to the spiritual needs of his thousands of congregants. As a pop

icon and winner of multiple KORA awards (including Best Male Artist for 2003 for the whole African continent), George Okudi

regularly packs the halls and sings to crowds of tens of thousands of people. His song 'Wipolo' is a clever blend of both

of these sides of his life. A straight up modern african pop piece, this song is guaranteed to get anyone moving. This song

is also the song that won Okudi the PAM (Pearl of Africa) Award for best song, won the FM Best Single Award, and launched

Okudi to the KORA awards in 2003. So for those of you who know the song, but have not been able to find a copy, get it now!

For those of you who have never heard it, join the 800 million Africans who have by getting your own copy now!